The winter is, of course, what we consider the peak of the paddling experience. Usually by the summer when the Little White Salmon and the Upper Upper Cispus have dried up, all eyes turn to the west and we start cruising the surf reports and scoping out the wave forecasts on the Oregon Coast. For me, summer and fall means dusting off the playboat trying to find the perfect ocean wave.

There is something about kayak-surfing a big wave in the ocean that isn't matched by anything on the river; I've run drops up to 40 feet tall on creeks and that sensation pales in comparison to dropping in on a big wave and accelerating ahead of tons of water that will pound the hell out of you if you make a mistake; big waves are terrifying, alluring, and in the end, utterly irresistible.

![]()

A few years ago a big storm was brewing in the Pacific, and the waves running ahead of this monster could only be described as epic. I was in Newport with a few of the fellas and the surf was really big. We were alone on the beach, no one else in the water, except some fishing boats that were having a rather bad time of it. The Coast Guard was out in force, with a helicopter circling overhead with a rescue crew as the hapless fishing boats made their desperate runs past the Jetty; it was quite a scene. I don't remember the wave height that day, but they were the biggest I have ever kayak-surfed.

We stood around for awhile, staring at the magnificent maelstrom in front of us, feeling the air move as the waves broke, and generally getting psyched. After awhile we decided (against our better judgement) to give it a go.

It was hard to get out, but we were experienced enough to lurk in the middle zone between the breaking waves wait for an elusive opening. The trick was to time the sets and then scurry out past the break and avoid getting obliterated by what I called the 'Punisher Waves' which seemed to randomly materialize out of nowhere and blot out the sun.

Those of us unlucky enough to get caught by a Punisher had the breath sucked out of us as we cartwheeled endlessly under water, settling into inky blackness of deep water, not knowing which was up. I almost lost my paddle during one of these poundings, resurfacing shell-shocked with my nose gushing blood, hoping the local sharks weren't out looking for a snack.

I only made it past the break a few times that day, and each time the experience was so harrowing that I kept promising myself that I would ride 'just one more' then call it quits. But something kept drawing me back out..

After a few brutal poundings everyone else gave up and I was alone, out beyond the break. I knew I shouldn't be out there by myself, because it was definitely a day when you got out there and then started wishing maybe you hadn't made it.

Finally, I spotted a really big swell coming in; it was a monster, and I felt a blast of adrenaline as I turned and my paddle started churning as I sought accelerate and to match the wave's speed. Somehow, to me and my friends disbelief (they were watching from the jetty) I just happened to be in the right place at the right time, and all my paddling ended up being incidental.

The wave rose and peaked right under me, and I gleefully launched off the lip and dropped through the air, landing on the face hard enough ooof! that I felt the impact in my back, and then I was skipping madly across the face to the left, running like hell to keep ahead of the huge, curling pile that was chomping on my stern. It was an incredible ride that seemed to go on forever.. and ever.. and then I realized something was very wrong... because it really was going on forever..

I was now high up on the beach, and the pile was still going.. and going.. and going.. I was riding one of the true 'sneaker' waves that drown people walking on the beaches, and as this wave enveloped the entire beach I was still bouncing and skipping along the pile as dry sand sped by below..

Suddenly I saw a large driftwood log straight ahead, a twenty foot long, 3-foot diameter old growth monster embedded in the sand, and I was being propelled irresistably towards it by the wall of water! "Ahhh shiiit..." I thought. I only had a few seconds to react, so with a desperate burst of strength I took two hard strokes and lunged to the left as I shot past the jagged trunk, the sharp pieces of wood missing my chest by a hair's breadth..

The wave exploded into the log behind me, I remember being backwards at that point and seeing the water explode into the air and then the log disappeared, swallowed up in the churning mass of brown water.

Suddenly it was over, and I was high and dry. The wave receded, and I was sitting up high on the beach, far from the edge of the water. The instant transition from the surging, roaring maelstrom to the tranquility of sand and driftwood was totally disorienting, and for a second I just sat there, teetering between the two dizzying extremes.

I called it a day.

![]()

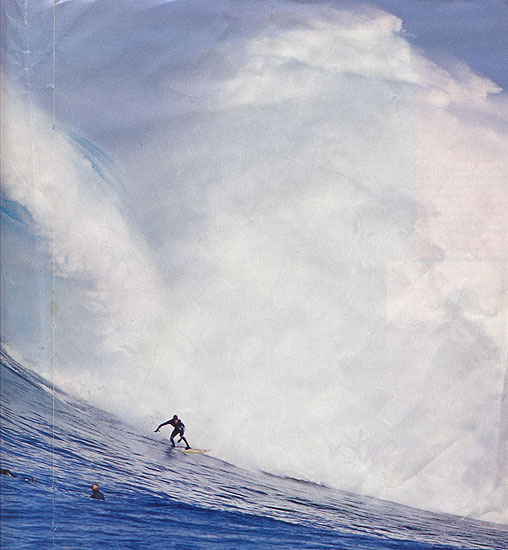

For the 'Taos' of the board-surfing world, the waves at the top end of my personal kayak-surfing scale are hardly worth mentioning. These guys are in a whole different, very scary world. The following photos were scanned from SURFING Magazine ( The best surfing mag there is, if you are looking to subscribe to one..)

The photos below show the largest wave ever surfed: A certified 66-footer, not entirely visible in this photo. The surfer is Mike Parson.. talk about nerves of steel! You can find these mind-bending monsters every few years when the conditions are right at The Cortes Break, which is 100 miles straight off the coast of San Diego. I guess there is a pinnacle of rock projecting up from the bottom of the ocean that creates a break of epic proportions.

The surfers ride short, fast, boards with foot-handles like wind-surfing boards to keep them from slipping as a fall could be fatal. After a 12-hour boat ride out to the break, these guys get towed by some very brave chaps on Jet-skis in order to build up enough speed as the waves crest; the Jet-Skis are then forced to outrun the wave, which reach speeds in excess of thirty miles per hour as they break...

On this particular day a smaller 50-footer outran one of the Jet-skis; as it broke the rider dove deep but the Jet-Ski was never seen again!

For more great photos of the Surfing Mag's annual 'big wave contest', click here

|

The 66-foot world-record breaking wave, shot from the front.. Photo: Surfing Magazine (obviously..)

|

Photo: Surfing Magazine  |

The Biggest waves are not always the best waves in my opinion; it's more about a well-formed wave that can be played on, and the frequency (or 'period') of the waves so you can get out beyond the break. My personal rule is: "I will ride no wave before it's time.." In other words, get out beyond the break and pick the wave you want, then ride it from the moment it forms... it's an unforgettable experience riding a wave from it's inception.

Remember, if you are looking for big waves, that each square foot of water weighs 64 pounds, so the big ones can literally drop tons of water on you. Unlike surfers, who dive under waves, kayakers are held on the surface, so we are much more exposed to injury that our board-riding brethren.

In my experience, high tide tends to be the best, especially if the beach gradually becomes shallow. Beaches of this variety have waves that 'crumble' as they come in, forming great piles and wide, deep faces for throwing down in.

The largest wave ever recorded occurred in 1737, when a monster Tsunami measuring 210 feet (64 meters), hit Siberia's Kamchatka Peninsula. (shortly after that, they renamed it the 'Kamflata' Peninsula.. =)

| My personal ratings for kayak-surfing | |||

| Class | Description | Wave Height | Commentary |

| I | Beginner | 2 - 3 feet | Ummm... no. |

| II | Novice | 3 - 5 feet | Mellow. |

| III | Intermediate | 5 - 7 feet | Can be sweet if well-formed. |

| IV | Advanced | 7 - 10 feet | The zone of best play. |

| V- | Expert | 10 - 15 feet | The injury zone. Tuck hard! |

| V+ | Getting scary | 15 - 20 feet | The danger zone. No Mistakes. |

| VI | Extreme | 20 + feet | Fun to look at.. from the shore. |

| Unreal | World Record (see above) | 66 feet | Ummm... no. |

Wave height is the distance from a wave's trough to its crest (i.e. amplitude).

The crest is the top of an unbroken wave, the trough is at the bottom of the front of the wave.

Wave period is the amount of time (in seconds) it takes from the moment one wave crest passes a fixed point until a second wave crest passes that same point. Typically one will hear waves described like, " It's 5 ft @ 13 seconds".

What this means is that the average height of the largest 33% of the waves are 5 ft and that the average period (time between wave crests) of the most prevalent swell is 13 seconds.

But waves measurements come in two flavors: Significant Seas and Swell. In general, if you have a choice between obtaining Significant Sea or Swell data, use Swell data. Significant Seas donít exist in the real world from a surfing perspective. "Seas" are the combined sum of the heights of all waves present at the reporting station.

Think of it as the average wave size. For example, it there is a 5 ft swell coming from the north, and a 3 ft swell coming from the south, it would be reported as a 6 ft sea. ('Seas' are actually the square root of the sum of the squares of all wave energy present). Add in a bunch of open-ocean chop and it really starts to skew the results. Surfers don't typically ride two separate waves coming from two different directions simultaneously. So the seas measurement is actually overstates actual wave size.